Treblinka: A Site of Memory and Mourning

Treblinka is one of the six major killing centers established by the Nazis in occupied Poland. Treblinka, along with Belzec and Sobibor, were an outgrowth of Operation Reinhard, representing a shift from the Holocaust by bullets to the Holocaust by gassing.

In January I visited Treblinka with my sister. We rented a car in Warsaw and drove 111 kilometers to Treblinka. Located in the northeastern part of the country just an hour away from the Ukrainian border, Treblinka is encumbered by the forest, located in the middle of nowhere.

With fresh snow on the ground and a wind chill of 15 degrees, we visited the grounds at Treblinka. Unlike Auschwitz where barracks and crematorium have been preserved, there are no Holocaust remnants at Treblinka. Between July and August 1944, the Nazis destroyed all traces of the camp as the Soviet Red Army drew near. The Treblinka Museum provided a map which corresponded to a standing guide near the memorial, allowing us to visualize where certain structures—the labor camp (Treblinka I) extermination camp, (Treblinka II) and execution site once stood. However the majority of Treblinka’s memory is taken up by its memorial designed by Franciszek Duszeńko, Adam Haupt and Franciszek Strynkiewicz, who designed the tall monument at the center of the memorial structure, constructed to bear similarity to Jerusalem’s Western Wall. Built at the site of Treblinka II and unveiled on May 10, 1964, the memorial consists of 17,000 stones placed atop 22 square meters of concrete which covers the ashes of the between 700-900,000 murdered. Amidst the stones rests 11 boulders each engraved with the name of a different country from which the murdered Jews held origins.

Experiencing Treblinka Firsthand

When we arrived we were told which areas could be viewed by foot versus on wheels. We ended up walking part of what should have been driven. As Tillie and I entered the forest our hands and feet went numb, we lost cell service. If I was on my own, I would have been lost, stuck in a forest of Holocaust confusion, unable to escape the past. However Tillie’s navigational skills superseded my own, identifying areas of death now replaced by nature.

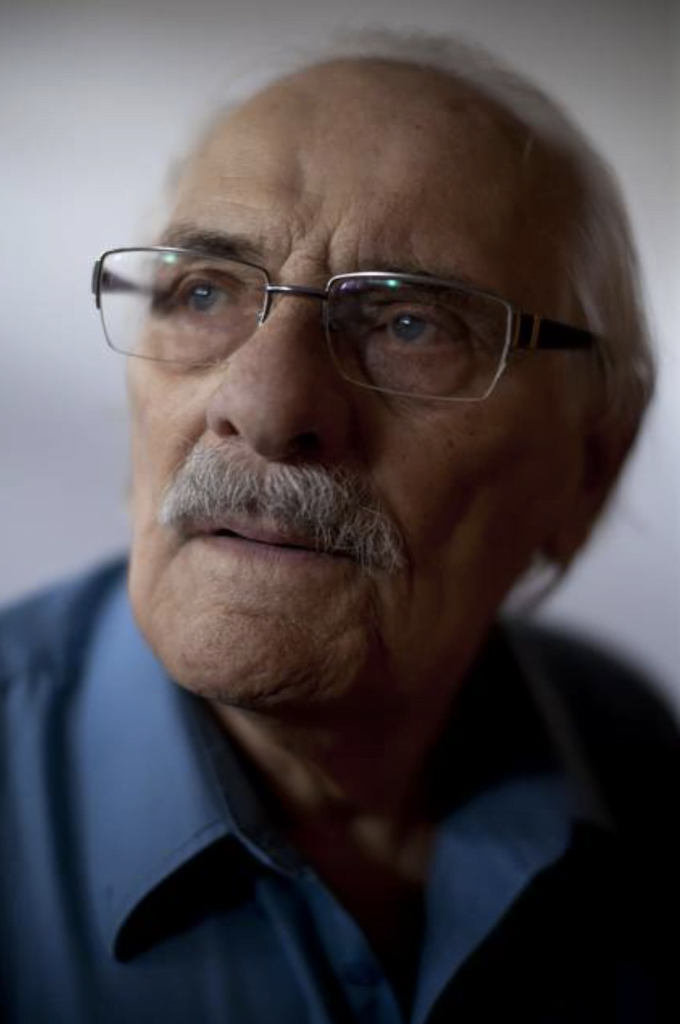

Being there now felt like sheer luck, as if our collective good fortune was the byproduct of bad timing. We couldn’t see or even imagine the brutality. Samuel Willenberg taught us that in the informational video the front desk employee has us watch upon arrival. And it’s on this day in 2016 the world lost that man, writer and artist Samuel Willenberg, a Polish descendant and Holocaust survivor who served as a Sonderkommando at Treblinka and took part in its revolt in August 1943. Born in Częstochowa, Poland, Willenberg’s life changed forever with the Nazi invasion in September 1939. After a harrowing encounter with the Red Army near Chelm, he escaped Soviet captivity and reunited with his family.

The Legacy of Samuel Willenberg

In 1940, Willenberg and his family faced the brutal realities of the Opatów ghetto, established in spring 1941. Despite the dire conditions, they survived through bartering his father’s paintings. In October 1941, during Operation Reinhard, the Nazis’ mission to exterminate Polish Jews, the Willenbergs obtained false papers but were eventually caught. On October 20, 1942, Willenberg was among 6,500 people deported to Treblinka.

At Treblinka, wearing his father’s paint-stained clothes, he was advised to pose as a bricklayer, saving him from immediate death. Tragically, he discovered his sisters’ clothing among the possessions of the dead, confirming their fate. Assigned number 937 in the Sonderkommando, he was forced to partake in the camp’s darkest tasks.

Willenberg’s moment of defiance came on August 2, 1943, during the Sonderkommando revolt. He was one of the few who escaped, sustaining only a leg injury. He found his father in Warsaw and joined the underground resistance, adopting his mother’s maiden name, Ignacy Popow.

After the war, from 1945 to 1946, Willenberg served in the Polish Army and helped locate Jewish children hidden during the war. He married Ada, a Warsaw Ghetto escapee, and in 1950, they moved to Israel. There, he worked as an engineer and graduated from Hebrew University with a degree in fine arts. His sculptures, reflecting his Treblinka experiences, gained worldwide acclaim.

Willenberg’s journey from the horrors of Treblinka, where he spent 10 months and was one of only 67 survivors, to his post-war achievements, is a story of extraordinary resilience and courage.

“My artistry is my memory – my ability to remember what my eyes saw… I remember pictures. I see the pictures from “there”, even today.”

References

- Culture.pl (April 23, 2003). “Treblinka. Rzeźby więźnia Samuela Willenberga” [Sculpture by prisoner Samuel Willenberg]. Multimedia. Adam Mickiewicz Institute. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- M.P.W. (2013). “Samuel Willenberg“. Powstańcze biogramy. Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- “Jewish History of Opatów. Part 1 to 5“. Virtual Shtetl (in Polish). Museum of the History of Polish Jews. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- The statistical data compiled on the basis of “Glossary of 2,077 Jewish towns in Poland” Archived 2016-02-08 at the Wayback Machine by Virtual Shtetl Museum of the History of Polish Jews (in English), as well as “Getta Żydowskie,” by Gedeon, (in Polish) and “Ghetto List” by Michael Peters at www.deathcamps.org (in English). Accessed August 29, 2013.

- “Częstochowa ghetto“. History. Virtual Shtetl Museum of the History of Polish Jews. p. 4. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- Stawsky, Gerardo (June 11, 2009). “Despite Treblinka. Protagonists“. Teaching the Holocaust to Spanish speakers. ORT Uruguay University’s Film Department. Archived from the original on June 11, 2009 – via Internet Archive.

- Treblinka Museum Commemoration Information

- May 10, 1964 Unveiling of the Commemoration of Treblinka II Extermination Camp

- Treblinka: A Place of Remembrance

- Interviews with Samuel Willenberg