Initial Thoughts on Auschwitz Visit

It all began with a walk through the infamous Arben Macht Frei Sign, the entrance to Auschwitz I, which opened on June 14, 1940. The tour guide did not mention that the original was stolen and that we were looking at a replica or more importantly, that the majority of its prisoners did not enter or ever see this sign, leaving visitors with the impression that they did. The Auschwitz album, a part of the Auschwitz Museum building, did a strong job of narrating the different aspects of the camps, presenting various photographs which demonstrated Nazi brutality.

Two photographs showed Jews arriving at Auschwitz, awaiting the selection process at Birkenau, the guide identifying the chimneys to Crematorium 2 and 3, distinctly placed in the background. Such photographs shed light on individual stories of Jewish tragedy; a mother and her five children before being sent to the gas chamber, secret photos taken by Sonderkommando which represent the only photographic evidence of the crematoria operational.

There was a strong fetishization of death (or life) in the form of specific artifacts. A case presenting a blanket made from human hair next to tons, full of human hair, 80K pounds of shoes, a mountain of eyeglasses, a dump truck four feet deep and 20 feet wide full of pots and pans. These represented just some of the belongings of those imprisoned at Auschwitz. The Museum exhibit continued in several buildings, supplemented by key facts and statistics.

It was chilling to walk through the crematorium and gas chamber connected to Auschwitz I, first used in September 1941. It was a solemn walk through a dark corridor that led to the last remaining structure of its kind intact since the time of its use.

Our tour guide said that 75% of Auschwitz I was authentic to the period. This especially referred to the blocks, of which there were 28. While 25% of the insides had been rehabilitated to account for upkeep, much of Block 11, known as the Death Block, remained intact. Before entering we were told that no one who entered Block 11 came out alive which were odd words to hear for those of us visiting 80 years later.

Auschwitz Birkenau, 90% of which remained intact, was discussed by the tour guide as an entirely separate entity. While technically true, it was partially misleading given the robust nature of the Auschwitz concentration camp complex. Our driver dropped us off in the nearby parking lot.

Walking Through Birkenau

What followed was a 3-minute walk to the infamous gates to Birkenau, which to this day, serves as the most famous image of Auschwitz, and to a great extent, the Holocaust as a whole. Once through the gates, it was easy to see how vast Birkenau was. It was enormous while also permanently incomplete. The Nazis never finished the complex in time. And yet, it looked identical to the photographs from the period. While parts of the train tracks running through the main gate had since been replaced, the ground and the brick barracks that covered the camp were original. A Holocaust era railway car stood at the point of arrival where new transports would get off at Birkenau. Walking these grounds was eerie. While our group was standing there, we were reminded of the photograph from the Auschwitz Album showing the transport to Birkenau waiting for selection. All of a sudden, we were there, albeit some 8 decades later.

While the majority of the wooden barracks have since disintegrated, the forests of brick chimneys remained intact in the distance. As we walked the camp’s expansive 3 kilometers, we came to the two sites of destruction, Crematorium II and III, both destroyed by the Nazis before the Axis retreat from the region. While the clouds, a perfect shade of gray, hovered above for the duration of the tour, the storm clouds quickly moved in, giving way to heavy rain and wind. The ghastly site of each crematorium, imbued the impression of fresh destruction. While each were blown up over 8 decades ago, it presented as if it were yesterday. Indeed, the preservation of destruction, added to its raw reality, its perverse artsy quality suggested the perfection of destruction, the fragmented crematoria and gas chamber perfectly resting opposite one another, mountains of bricks scattered amongst the ruins. And while restoration efforts have been carried out on several occasions, the dilapidated structure remains transfixed in time, preserved for the sake of future witnesses.

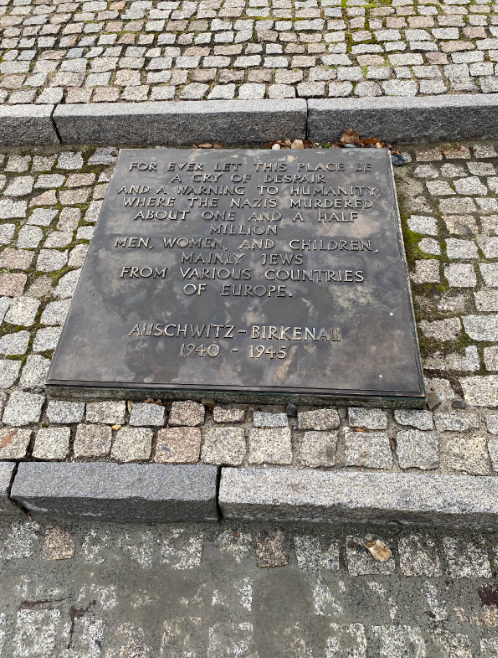

The International Monument to the Victims of Fascism

As our tour grew colder, we observed the Auschwitz monument separating crematorium II and III. Erected in 1967 after 9 years of work, with a design by Andrea and Pedro Cacella and implementation by Herzy Jarnusczkiewicz, Julio Lafuente and Giorgio Simoncini, The International Monument to the Victims of Fascism is a monument constructed through abstraction. And while its interpretations remain multifold, when observed up close, its structure evokes the non-linear nature of genocide. Henry Moore, a British sculptor and chair of the monument’s selection committee alluded to the task’s impossible nature. No sculpture could embody what took place at Auschwitz. At the monument’s base lies 23 plaques, representative of the 23 different languages spoken by those murdered at Auschwitz, inscribed with the following message:

For ever let this place be a cry of despair and a warning to humanity Where the Nazis Murdered about one and a half million men, women and children, mainly Jews from various countries of Europe. Auschwitz-Birkenau 1940-1945

The International Monument to the Victims of Fascism is a strong example of a counter-monument, a memorial structure which betrays the traditional conventions of memorial remembrance. This is exemplified through its abstraction, which, when presented through an anti-monument, acts as the form of rebellion against traditional Nazi structures. Issues of completeness and closure, discussed by Holocaust scholar James Young who coined the term counter-monument, are not the concern of such structures which exist in order to subvert traditional understandings of artistic form and representation.

Conclusion of the Visit

We ended our tour in a women’s barracks built by Soviet POWs. We were told that unlike other blocks and barracks, this one lacked a stable foundation, making it harder to brave the elements, disease, and overpopulation. As our visit concluded, we learned that Auschwitz’s continued existence, as a museum and site of historical atrocity, can be credited to Holocaust survivors who fought for its preservation. It was Natan Blumenthal, founding member of the Central Jewish Historical Commission and Tadeusz Wąsowicz, the first director of the Auschwitz State Museum, that pushed for preservation, remaining integral to the entire process. Auschwitz was built by Nazis with the intent of exterminating all Jews and eventually, the structure that made it possible. They succeeded at neither. Jews not only helped win the war, but ensured its evidence not be left behind.

Addendum

It is impossible to commemorate International Holocaust Remembrance Day without recognizing the 21st century slaughter of Jews that took place on October 7th, 2023. What took place on that day was a pogrom of vicious magnitude and served as a gruesome reminder that a people which number .02% of the global population remain the world’s prime target. But the October Pogrom was more than that. Fourteen hundred Jews were murdered that day, more than any single day since the Holocaust. They were targeted for merely existing as Jews. As of this writing, the world, much like it did during the Holocaust, has turned its attention elsewhere and chosen to forget about the 150 Jews crying out for life—humans reduced to hostages in the wake of the October Pogrom. Instead of international cooperation and acceptance, the world has responded through competition and antisemitism where victim totals are disputed, deaths are denied and posters are vandalized, the despaired now viewed as a distraction. It calls to mind what the Australian Parliamentarian T.W White said at the Evian Conference in July 1938: We don’t have a Jewish problem and we don’t want to import one. Let’s make sure BringThemHomeNow doesn’t go the way of NeverAgain.